The Camel Postman

Peter Symes

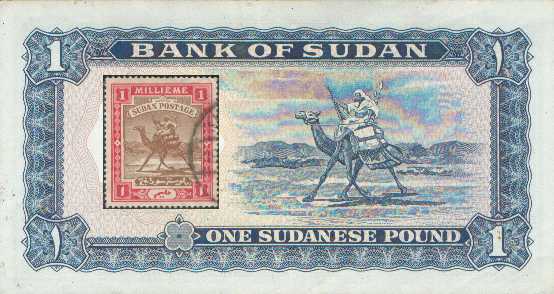

Sudan has been prolific in its output of banknotes since it first began issuing paper money in April 1957. In contemplating the notes that have been issued over the years, it is difficult to identify any single element in the designs that can be consistently associated with Sudan. The current notes have an illustration of the Republican Palace in Khartoum, while earlier issues used a circular device that contained an outline of the country, a picture of the headquarters of the Bank of Sudan, or the portrait of President Ja’afar al-Nimeiri. One of the more intriguing symbols to have been used on Sudanese banknotes is the ‘Camel Postman’, which was used on the notes issued by the Sudan Currency Board and on the first banknotes issued by the Bank of Sudan. Although illustrated on the earliest Sudanese banknotes, the history of this image begins over fifty years earlier, with the postage stamps of Sudan.

In the dying years of the nineteenth century, Great Britain was attempting to overthrow the Mahdist regime of Sudan. Sudan had been controlled for many years by the Mahdi, who had defeated and killed General Gordon following the Siege of Khartoum in 1884 and 1885, but the British had returned and, by the late 1890s, had all but subjugated the country. In charge of the British forces in Sudan was Sir Herbert Kitchener, later to become Lord Kitchener, and as his grip on Sudan increased he began to look to administrative matters.

Sudan must have its own postage stamps, rather than use those of Egypt, and Sir Herbert commenced the process of obtaining a suitable design. A well-known artist travelling in the region at the time was asked to submit a design, but his depiction of the rock temple at Abu Simbel was not utilized. It is not known whether the design was rejected because Abu Simbel was located in an area that could be claimed by the Egyptians or because the artist demanded payment of twenty-five guineas. However, having rejected this particular solution to his problem, Sir Herbert called upon the services of Captain E. A. Stanton.

In 1897 Captain Stanton was stationed with General Macdonald’s Sudanese Brigade at Korti in the province of Dongala. His duties included surveying and mapping the region. Being an amateur artist and finding himself with time on his hands, he took to drawing illustrations of oases, wells, and points of interest in the margins of the maps he was helping to create. These pen-and-ink sketches came to the attention of Sir Herbert, who made a point of meeting Captain Stanton on his next visit to Korti.

On meeting Captain Stanton, Kitchener ordered him to provide a design for a postage stamp and promptly gave Stanton a generous five days to complete the design. Inspiration eluded Stanton for several days, until the regiment’s mail was delivered by camel instead of the usual river steamer. As well as being a map-maker, Stanton was also the liaison officer for the local tribesmen, which included the Howawir tribe. Therefore, he was able to prevail on the Sheikh of the Howawir tribe to don his war kit and mount his camel, so that he could draw his inspired image of the ‘Camel Postman’. In order to make the camel appear to be on a postal run, bags filled with chopped straw were attached to the saddle to imitate mailbags. Stanton then drew the sketch of the Sheikh riding through the desert and added the names of ‘Khartoum’ and ‘Berber’, two towns in Sudan, to the mailbags.

To Stanton’s great relief, Sir Herbert accepted his drawing and, in March 1898, postage stamps prepared by Thomas de la Rue with Stanton’s illustration were issued at Berber. The ‘Camel Postman’ continued to be used on Sudan’s postage stamps for the next fifty years, although other designs were periodically utilized. When Sudan prepared its first banknotes, the Camel Postman was chosen to adorn the back of the notes.

It is not known who decided to place the Camel Postman on the back of the banknotes, but it had become such an identifiable image of Sudan, that there could have been no better image to choose. The first banknotes prepared for issue in Sudan were never released into circulation. These notes were printed by Waterlow and Sons of London and were to be issued under the authority of the Government of Sudan. However, there was a delay in the issue of the notes, due to difficulties with Sudan and Egypt negotiating the withdrawal of Egyptian currency, which was then circulating in Sudan. By the time negotiations were complete, the Sudan Currency Board had been established and there had been a change of government in Sudan. Because the signature of the previous Prime Minister appeared on the yet-to-be-issued notes, the new Prime Minister ordered the banknotes to be destroyed. A new series of banknotes was subsequently prepared by Thomas de la Rue and issued in April 1957 by the Sudan Currency Board.

In 1960 the Bank of Sudan was established and it soon issued banknotes under its own authority, having initially used the notes of the Currency Board. The design of the new notes was similar to those issued by the Currency Board, with only slight changes to the text. These notes remained in circulation until 1970 when the Bank of Sudan’s second series of notes was introduced. This ended a fourteen-year period in which the Camel Postman travelled throughout Sudan on the back of every banknote.

The original sketch for the Camel Postman was last recorded as being in the possession of the Government of Sudan and it is an important relic of their history, as its use was so widespread. The Camel Postman not only appeared the postage stamps and banknotes of Sudan, it also appeared on coins issued in Sudan from 1956 to 1970. While now no longer to be found on postage stamps, coins, or banknotes circulating in Sudan, for over seventy years the Camel Postman was the most identifiable symbol of Sudan and it is still useful to the collector in identifying coins, stamps and banknotes issued in Sudan.

Note: The Image of the 1-pound banknote has a postage stamp super-imposed over the watermark, showing how the original drawing was utilized.

This article was completed in March 2003

© Peter Symes