Habib Lotfallah and the Arabian National Bank of Hedjaz

Peter Symes

The Mystery

The banknotes of the Hedjaz![]() first came to the notice of the international collecting community in 1954 when four notes were offered for sale in the auction of King Farouk’s numismatic collection. These notes were included in a 350-piece lot of paper money that sold for about US$160.00. While this brief mention of the notes was probably overlooked by many people at the time, the notes prepared for the Arabian National Bank of Hedjaz soon became an enigma amongst collectors.

first came to the notice of the international collecting community in 1954 when four notes were offered for sale in the auction of King Farouk’s numismatic collection. These notes were included in a 350-piece lot of paper money that sold for about US$160.00. While this brief mention of the notes was probably overlooked by many people at the time, the notes prepared for the Arabian National Bank of Hedjaz soon became an enigma amongst collectors.

The notes are an enigma for a number of reasons. Firstly, the notes were never issued, with only unissued and specimen notes being known. Secondly, there had been nothing reported of the issuing authority, which appeared never to have existed. Finally, the illustrations on the banknotes include decorations and illustrations of scenes that are not in, or of, the Hedjaz. Why would someone prepare notes for issue in the Hedjaz and then place scenes from Lebanon, Syria, and Iraq on the notes?

The mystery surrounding these notes has in part been due to their infrequent appearance on the collector market. One of the few recorded sales of a note was during the 1980s when the American dealer Ted Uhl sold a 100-pound note without serial numbers. During the 1990s copies of unissued notes were offered for sale in the United States of America. The set consisted of the five denominations of 1, 5, 10, 50 and 100 pounds.

Like so many enigmas, once the truth is told about these notes, all becomes so clear that it can only be wondered why the reason for the existence of these notes has remained obfuscated for so long. As it transpires, the story of the banknotes revolves around the ambitions of one man

and once his story has been told the history of the notes will be revealed. The gentleman

responsible for establishing ‘The Arabian National Bank of Hedjaz’ and for preparing its

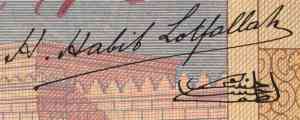

banknotes was H. Habib Lotfallah, and his signature is apparent on the banknotes prepared for

the bank. The banknotes were his, the issuing authority was his, and this is his story.

Like so many enigmas, once the truth is told about these notes, all becomes so clear that it can only be wondered why the reason for the existence of these notes has remained obfuscated for so long. As it transpires, the story of the banknotes revolves around the ambitions of one man

and once his story has been told the history of the notes will be revealed. The gentleman

responsible for establishing ‘The Arabian National Bank of Hedjaz’ and for preparing its

banknotes was H. Habib Lotfallah, and his signature is apparent on the banknotes prepared for

the bank. The banknotes were his, the issuing authority was his, and this is his story.

Habib Lotfallah

The Lotfallah family were Syrians of the Greek Orthodox Church and the modern history of the family begins with Habib Lotfallah, who was born in Beirut on 5 May 1826. Habib Lotfallah, who is not the hero of this story, was nevertheless a most remarkable man and he lay the foundation for this story. Educated in Beirut he travelled to Egypt in 1852 to make his way in life. Backed by substantial capital, he and his brother Mikhail commenced commercial enterprises that steadily grew until they encompassed interests in Egypt, Sudan and India. Their enterprises in Sudan became considerable and their wealth steadily increased. However, Mikhail Lotfallah died and Habib Lotfallah decided to forgo the commercial world and turned instead to agriculture.

Purchasing substantial land holdings in the Nile valley, he developed them so that their productivity increased and over time he acquired more land, which ultimately made him one of the greatest landowners in the Nile valley. By 1905, when he retired from business, he was one of the wealthiest men in Egypt. Not only was he wealthy, but he had won the respect of the government, which made him a ‘Pasha’, and he had become renown for his beneficence and charitable deeds.

Habib Lotfallah Pasha had three sons: Michel, Habib and George. In 1905, after their father’s retirement, the three sons took over the family business, but their father remained the head of the family and he continued to be active in many fields. In 1920 Habib Lotfallah Pasha was created an Amir by King Hussein of the Hedjaz. The award of the title ‘Amir’ to Habib Lotfallah Pasha was due to a number of factors, but importantly it demonstrated a link between the Lotfallah family and the Hashimite King of the Hedjaz and his family. When the Hedjaz was freed from the suzerainty of the Ottoman Empire after the Great War, King Hussein found himself an independent monarch (albeit under the protection of the British). Hussein decided to introduce his own orders and decorations and to suppress the Ottoman titles—such as ‘Effendi’, ‘Bey’ and ‘Pasha’. Two of the orders he created were the ‘Nahda’ (awakening) and the ‘Istklal’ (independence). The honorary title that he chose to ennoble the most distinguished recipients of his awards was ‘Amir’. Hussein was reasonably generous with his honours and awards, presenting orders and decorations to a number of Syrian, Egyptian, Italian and British recipients.

In the official gazette of Mecca, published on 16 Ramadan 1338 (3 June 1920), the following grant was announced:

‘The title of Amir is granted to El-Sayed Habib Lotfallah. Here is a copy of the pertinent Royal Edict:

‘In view of the antiquity of the Lotfallah family and in view that We know of the consideration that he enjoys among his fellow countrymen, grant the title Amir to El-Sayed Habib Lotfallah, which is transferable to his progeny from father to son until it pleases God.’

The title was recognition for the support that Habib Lotfallah Pasha had given to charitable projects; of the support the family had given to Syrian nationalist and independence movements; for the hospitality that the family had shown to Abdullah, the son of Hussein, on a visit to Egypt; and because of the distinguished character of the recipient.

Habib Lotfallah Pasha died on 28 December 1920 at the age of ninety four. At his funeral

the King of the Hedjaz was represented by Nuri al-Said, who later became Prime Minister of

Iraq. Following Habib Lotfallah’s death, the estate of the family was managed by his three sons.

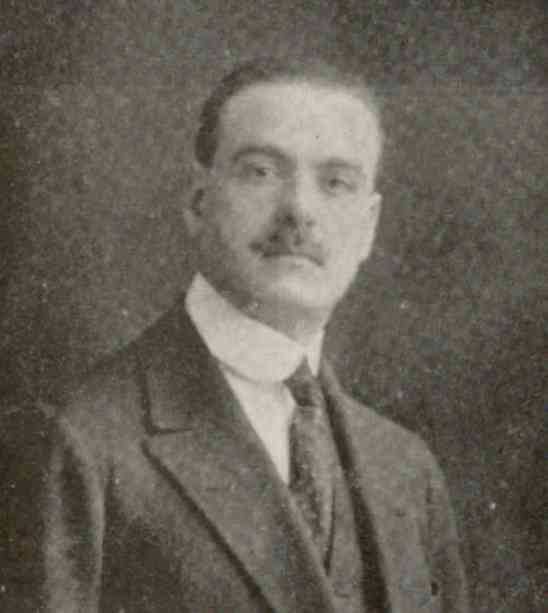

Of the three sons, it is the fortunes of his second son, H. Habib Lotfallah

![]() , which are of singular

interest to this history.

, which are of singular

interest to this history.

H. Habib Lotfallah was born in Cairo in 1882. After completing some schooling in Egypt, he went to France for three years to complete his studies; after which he visited various European cities before returning to Cairo. He attended the Military Academy and in 1907 he was commissioned as a sub-lieutenant in the cavalry of the Egyptian Army

H. Habib Lotfallah was born in Cairo in 1882. After completing some schooling in Egypt, he went to France for three years to complete his studies; after which he visited various European cities before returning to Cairo. He attended the Military Academy and in 1907 he was commissioned as a sub-lieutenant in the cavalry of the Egyptian Army

![]() . However, he was not

satisfied with a military life and in 1908 Habib Lotfallah sought a career as a diplomat in the

Ottoman Empire. In pursuing this aim, he visited the Balkan states before continuing to Austria,

Germany, Italy, France and Spain. In 1911 he was appointed Treasurer to the authority that

supervised the injured of Beirut following attacks on that city during the Italo-Turkish war. In

1912 Habib Lotfallah was appointed an inspector of the Red Crescent so that he might

investigate matters relating to the injured during the war that took place in the Balkans in that

year. In 1913 he was appointed Attaché to the Embassy of Turkey in London when Tewfik Pasha

was the Turkish Ambassador. However, he did not take up the appointment due to the war in the

Balkans and he remained in Constantinople, working in the Foreign Office. The following year

he became Attaché to the Grand Vizier Prince Saïd Halim in Constantinople and later he became

deputy envoy to the Wali

. However, he was not

satisfied with a military life and in 1908 Habib Lotfallah sought a career as a diplomat in the

Ottoman Empire. In pursuing this aim, he visited the Balkan states before continuing to Austria,

Germany, Italy, France and Spain. In 1911 he was appointed Treasurer to the authority that

supervised the injured of Beirut following attacks on that city during the Italo-Turkish war. In

1912 Habib Lotfallah was appointed an inspector of the Red Crescent so that he might

investigate matters relating to the injured during the war that took place in the Balkans in that

year. In 1913 he was appointed Attaché to the Embassy of Turkey in London when Tewfik Pasha

was the Turkish Ambassador. However, he did not take up the appointment due to the war in the

Balkans and he remained in Constantinople, working in the Foreign Office. The following year

he became Attaché to the Grand Vizier Prince Saïd Halim in Constantinople and later he became

deputy envoy to the Wali

![]() of Beirut, Békir Samy Bey.

of Beirut, Békir Samy Bey.

Some time after the outbreak of the Great War, when Habib Lotfallah returned to Cairo, he was advised by the British General Sir John Maxwell that it would be sensible to go quietly to neutral Spain and stay there until the war was over. Ostensibly Habib Lotfallah was still a diplomat in the employment of the Ottoman Empire, but it seems that by 1916 he had resolved that the days of the Ottoman Empire were over. Consequently, H. Habib Lotfallah spent the duration of the war in Madrid, where he associated with a number of notables who were similarly seeking to wait out the war. Once the Great War had ended, Habib Lotfallah returned to diplomatic duties. The Party of Syrian Union, in which his brother Michel was active, asked him to become its representative in Paris and London.

So successful was the work of H. Habib Lotfallah perceived to be, in representing the Party of Syrian Union, that, on his return to Cairo, he was asked by King Hussein of the Hedjaz to work for his family. In 1920 he was appointed adviser to Amir Faisal, a son of the King, and in the following year he was nominated as the head of mission and envoy for King Hussein to Paris and London. On 27 December 1920 (27 Safar 1339), Habib Lotfallah was awarded the Order of the Nahda for his services, loyalty and devotion to the King. In 1922 he became the foreign affairs adviser to the Kingdom of Arabia and then Chief aide-de-camp to King Hussein, with the rank of General. In 1923 he became Minister Plenipotentiary for the Hedjaz and Envoy Extraordinary to the King of Italy in Rome. The following year, in 1924, Habib Lotfallah led the Hedjazi mission to the League of the Nations in Geneva and was also appointed Minister to Moscow and Rome.

From the activities of Habib Lotfallah, from 1912 to 1924, it can be seen that he spent much of his time in Europe and he increasingly became a confidant of King Hussein. Because his father had been given the title of ‘Amir’, Habib Lotfallah used the title ‘Prince’ when moving amongst the diplomatic and social circles of Europe. The use of the title was perhaps not quite correct, but in Europe where princes were common, it appears to have been accepted without question.

King Hussein and the Hedjaz

The story of King Hussein is important to this story for a number of reasons. Firstly, his ideal of an Arab nation was shared by many people, including Habib Lotfallah. The divisions wrought on the Arab people by the colonial powers after the Great War were considered by many to have

destroyed an opportunity to unite the Arabs under one nation or in a confederation. Secondly, it

was under the administration of King Hussein’s son that the Arabian National Bank of the

Hedjaz was formed. Thirdly, it is because of the actions of King Hussein that the notes of the

Bank were never released into circulation. Finally, for a number of years Habib Lotfallah had

linked his fortunes to the Hashimite dynasty and it is therefore worth noting a few details of the

history of King Hussein and the Hedjaz.

The story of King Hussein is important to this story for a number of reasons. Firstly, his ideal of an Arab nation was shared by many people, including Habib Lotfallah. The divisions wrought on the Arab people by the colonial powers after the Great War were considered by many to have

destroyed an opportunity to unite the Arabs under one nation or in a confederation. Secondly, it

was under the administration of King Hussein’s son that the Arabian National Bank of the

Hedjaz was formed. Thirdly, it is because of the actions of King Hussein that the notes of the

Bank were never released into circulation. Finally, for a number of years Habib Lotfallah had

linked his fortunes to the Hashimite dynasty and it is therefore worth noting a few details of the

history of King Hussein and the Hedjaz.

When the Ottoman Empire held the Hedjaz, they ruled it in a similar manner to their other vilayets (provinces). There was however a significant difference. Unlike other vilayets, the Hedjaz had a temporal leader in the form of the Ottoman Vali, who was usually stationed at Medina, and the spiritual leader of Mecca, who was the Sharif. However, the lines between the spiritual and temporal powers of the Sharif of Mecca were often blurred and the Sharif occasionally sought more temporal control than he was allowed.

The Sharifs of Mecca were descendants of Hashim ibn ‘Abd Manaf, the grandfather of

the Prophet Mohammed (peace be upon him), whose daughter Fatima had two sons, Hussein and

Hasan. Descendants of the two clans competed for control of areas in the Hedjaz but, from 968

until 1925, Mecca was controlled by the Hasan clan, with competition within the clan for the

positions of Amir and Sharif

![]() (or Grand Sharif) of Mecca. During the rule of the Ottomans,

selection of the Sharif of Mecca was controlled through the central administration in

Constantinople. Although his grandfather and uncle had been Sharifs of Mecca, there was no

certainty that Hussein would attain the position. However, circumstances and successful intrigues

at the court in Constantinople saw Hussein appointed as Sharif in November 1908. Hussein was

an ambitious if ineffective ruler. From the time he became Sharif, he conspired to gain powers

from the Ottoman Vali; he moved to wrest control of Asir (to the south of the Hedjaz) from the

Idrisi; and he sought to expand his influence into the Nejd, which was controlled by ‘Abd al-Aziz

ibn Sa’ud.

(or Grand Sharif) of Mecca. During the rule of the Ottomans,

selection of the Sharif of Mecca was controlled through the central administration in

Constantinople. Although his grandfather and uncle had been Sharifs of Mecca, there was no

certainty that Hussein would attain the position. However, circumstances and successful intrigues

at the court in Constantinople saw Hussein appointed as Sharif in November 1908. Hussein was

an ambitious if ineffective ruler. From the time he became Sharif, he conspired to gain powers

from the Ottoman Vali; he moved to wrest control of Asir (to the south of the Hedjaz) from the

Idrisi; and he sought to expand his influence into the Nejd, which was controlled by ‘Abd al-Aziz

ibn Sa’ud.

The aspirations of Sharif Hussein were tempered by many factors until the outbreak of World War I. It was then that the British sought to encourage Hussein to raise the tribes under his control against the Ottomans. This resulted in the Arab Revolt which has been immortalized in the activities of Colonel T. E. Lawrence—Lawrence of Arabia. However, the Arab Revolt was a success because of Hussein’s sons, particularly Faisal, rather than any participation by Hussein. Indeed, Hussein’s ineptitude and narrow focus on his own ambitions often put the Revolt in jeopardy.

The British were responsible for financing the Revolt and poured gold into Hussein’s

coffers so that he could buy the allegiance of Arab tribesmen. This money replaced the subsidies

that had previously been supplied by the Ottomans, who had supported the Sharif of Mecca

because of the unique position Mecca held in the religion of Islam. In dealing with the British,

Hussein sought to confirm his own ambitions, which were to unite the Arab world under his

control, once the Ottomans had been defeated. To many Arabs, there was a nationalist ideal that

all Arabs, from Aden to Gaza to northern Mesopotamia, should unite as a single nation—an Arab

nation. Hussein nurtured an ambition that he should rule over such a nation or, as he perceived

it, a kingdom. To this end he proclaimed himself King in 1917, but not just ‘King of the Hedjaz’

as most observers might have expected, rather he announced his grand intentions by adopting the

title of ‘King of the Arab Countries’. He attempted to gain British support for his claim to this

title but the British were extremely reluctant to support his ambitions because they were

supporting many other Arab leaders and they did not wish to push the claims of one leader

against another. Hussein’s claim necessarily caused concern amongst states in the Arabian

Peninsula, such as the Nejd, Asir, Jebel Shammar, Kuwait, Oman, and Yemen, as they feared an

expansionist policy of King Hussein.

![]() Hussein did harbour dreams of expanding his influence

over Asir and into the Nejd and he probably dreamed of greater ambitions. Perhaps his ambition

in 1917 had some substance, as his son Faisal, after an abortive attempt to make him the King

of Syria, was appointed King of Iraq in 1921 under the British mandate and another son,

Abdullah, was recognized as Amir of Transjordan by the British in 1923. Therefore, the

possibility of uniting all Arab countries under one family was not altogether out of the question.

However, in 1917 Hussein chose not to revoke his self-proclaimed title of ‘King of the Arab

Countries’, which was ultimately ignored by friend and enemy alike, although it was given filial

support by the future leaders of Transjordan and Iraq.

Hussein did harbour dreams of expanding his influence

over Asir and into the Nejd and he probably dreamed of greater ambitions. Perhaps his ambition

in 1917 had some substance, as his son Faisal, after an abortive attempt to make him the King

of Syria, was appointed King of Iraq in 1921 under the British mandate and another son,

Abdullah, was recognized as Amir of Transjordan by the British in 1923. Therefore, the

possibility of uniting all Arab countries under one family was not altogether out of the question.

However, in 1917 Hussein chose not to revoke his self-proclaimed title of ‘King of the Arab

Countries’, which was ultimately ignored by friend and enemy alike, although it was given filial

support by the future leaders of Transjordan and Iraq.

There was yet another title that Hussein coveted, the title of Caliph. The Caliph was recognized by many Muslims as the temporal and spiritual leader of the Muslim community and for many years the title had been claimed by the Ottoman Sultans. Hussein believed that the title should belong to him, as the Sharif of Mecca, and as the Great War proceeded he eyed the prize with barely concealed ambition. However, although Hussein and his supporters intrigued for recognition of this ambition, the British only ever recognized him as King of the Hedjaz. Some years after the War, in 1924, Kemal Atatürk abolished the Ottoman Caliphate and, shortly after this announcement, Hussein declared himself the Caliph—although his claim was far from universally recognized.

Habib Lotfallah’s representation of the King of the Hedjaz at the meeting of the League

of Nations in Geneva in 1924 is another significant event in the ambitions of King Hussein. It

was Hussein’s desire to be seen as the only real power in Arabia and, as the Hedjaz had been one

of the twenty-seven ‘Allied and Associated Powers’ listed in the Treaty of Versailles as having

concluded the war

![]() , attendance at the conference in 1924 aided his bid for legitimacy. Such a

move was contrary to the previous conferences of the League of Nations, which were boycotted

by Hussein because the European powers had not given the Arabs the independence they craved.

However, by 1924 the tide was turning against King Hussein and it was more important that he

be represented amongst the European powers, than protest against their encroachment on Arab

ambitions.

, attendance at the conference in 1924 aided his bid for legitimacy. Such a

move was contrary to the previous conferences of the League of Nations, which were boycotted

by Hussein because the European powers had not given the Arabs the independence they craved.

However, by 1924 the tide was turning against King Hussein and it was more important that he

be represented amongst the European powers, than protest against their encroachment on Arab

ambitions.

In the years following the Great War, the British tired of King Hussein’s truculent ways and did not support him against his opponent ‘Abd al-Aziz ibn Sa’ud, who was becoming stronger as the months passed. Britain had been a strong supporter of ibn Sa’ud while he was in control of the Nejd and, now that ibn Sa’ud was pushing his way into the Hedjaz, they chose to withdraw support from King Hussein and let him fight his own battles. However, not only had Hussein alienated the British, he had also lost the confidence of the notables and merchants of Mecca. Under threat from an advancing ibn Sa’ud, Hussein first withdrew to Jeddah and then, on 6 October 1924, under pressure from ibn Sa’ud and demands from his own people, Hussein was forced to abdicate in favour of his son ‘Ali. Mecca fell to ibn Sa’ud on 18 October and ‘Ali became isolated in Jeddah. In as much a move of diplomacy as of strategy, ibn Sa’ud did not press his advantage over ‘Ali and he remained distant from Jeddah.

In October 1924 Habib Lotfallah was in Moscow as a guest of the government of the Soviet Union. His mission to Moscow was to establish regular economic and political relations between the Hedjaz and the Soviet Union. While he was in Moscow news of King Hussein’s abdication became known. For several days Habib Lotfallah refused to admit that the event had occurred, but ultimately he substantiated the facts and was able to confirm that his credentials as Minister Plenipotentiary were valid under King ‘Ali.

The numerous positions held by Habib Lotfallah from 1920 to 1924 and the missions he accomplished in serving his King in Europe appear to have left little time for him to attend the Hedjaz or to appreciate fully the circumstances as they were developing in the Arabian Peninsula. Whether, following the abdication of King Hussein, Habib Lotfallah fully understood the critical position in which King ‘Ali found himself, it is difficult to say. With three Hashimite kings in Arabia—‘Ali in the Hedjaz, Abdullah in Transjordan, and Faisal in Iraq—it may have seemed strange to Habib Lotfallah that any one of the Kingdoms was under threat. However, having fixed his allegiances and fortunes to the Kings of the Hedjaz, he stuck by their resolve to survive.

The Banknotes

Returning to the Hedjaz in 1925, Habib Lotfallah decided to pursue his Arab nationalist ambition of establishing a bank that would issue money throughout the Arab countries and his first target was the Hedjaz. There was no uniform currency in the Hedjaz and inept attempts at introducing a national coinage by King Hussein had not improved the situation. As one who had spent much of his adult life in Europe, Habib Lotfallah had come into daily contact with paper money and he would have understood the utility of such instruments. He should also have recognized that the lack of a modern currency in the Hedjaz was detrimental to the development of the economy, although he might also have realized that the introduction paper money was no panacea for the economic ills of the Hedjaz. However, before addressing the banknotes prepared by Habib Lotfallah, it is worth considering the currency circulating in the Hedjaz prior to his initiative.

Under the Ottomans, currency of the Empire circulated in the Hedjaz but, while coins are known to have circulated widely, it is not known to what extent the banknotes issued in Constantinople circulated in Arabia. Certainly the notes circulated, but the Arabs believed in currency that had intrinsic value and not paper that was backed by reserves and promises. For this reason, the Arabs preferred full-bodied coins of gold and silver; although Ottoman notes probably found favour amongst the merchants, traders and government officials. In coastal ports merchants and traders had come into contact with foreign currency, as had the many residents involved in supporting pilgrims with food, accommodation and guides during the annual Hajj to Mecca. This exposure to foreign currency included banknotes and, by the reign of King Hussein, Indian rupees and Egyptian pounds were in common use by merchants, traders and pilgrims.

However, the subsidy that Hussein had received from the Ottomans, as the Sharif of Mecca, was in gold and he needed this gold to dispense to tribal chieftains, as was his responsibility. When the British proposed that he forgo the Ottomans and rise against them in revolt, Hussein demanded that he be paid in gold by the British so that he could pay the tribes, just as he had done under the Ottomans. The British, locked in a war against the Ottoman Empire, agreed.

Although the British had secured the interests of King Hussein, they faced competition from their allies the French. The French were seeking to stake claims in the Arab world and they lost no opportunity to promote their own interests in the Hedjaz. In February 1917 the head of the French mission to the Hedjaz, Colonel Brémond, proposed to King Hussein that the French might mint coins for the Hedjaz, with the coins to be in a metric system, rather than based on the English pound. This proposal was rejected by Hussein, who preferred to follow the traditional use of full-bodied coins.

However, by June 1917 the British had paid out so much gold to Hussein from the

Egyptian treasury, that they asked Hussein if he might take payment in silver and paper money

in the form of Egyptian pounds and Indian rupees. In reply to the suggestion, an official in King

Hussein’s government wrote: ‘Paper money will assuredly cause bad effect, make people

attribute to us worse things than they attribute to Turks and our enemies will thus find a way of

saying all sorts of thing against us.’

![]() The tribesmen wanted only gold and their preference was

for British sovereigns. In October 1917 the British pursued the issue of paper money, due to the

dwindling reserves of available gold, and insisted that Hussein take part payment of his subsidy

in Indian rupee notes. They argued that he could sell the rupees to the merchants for gold, as they

needed rupees with which to trade. The British even offered to provide the rupees at a rate

advantageous to Hussein so that he might make a profit in selling the notes to the merchants.

The tribesmen wanted only gold and their preference was

for British sovereigns. In October 1917 the British pursued the issue of paper money, due to the

dwindling reserves of available gold, and insisted that Hussein take part payment of his subsidy

in Indian rupee notes. They argued that he could sell the rupees to the merchants for gold, as they

needed rupees with which to trade. The British even offered to provide the rupees at a rate

advantageous to Hussein so that he might make a profit in selling the notes to the merchants.

By September 1919 the availability of gold and silver had deteriorated to such an extent that the British were forced to provide the complete subsidy in Indian rupees. Although Hussein initially balked at this proposal, he turned the problem around so that, in January 1920, Hussein imposed the Indian rupee as the only legal tender in the Hedjaz. The merchants in Jeddah were not pleased with the rate of exchange that Hussein set between the rupee to the pound but, after some negotiation, an agreement was made and a rate set. Hussein then demanded that the merchants write to the British, stating that they agree to trade only in rupees—both in notes and silver. Although the Indian rupee had been declared the official currency, gold remained the measure of all currencies and pilgrims coming to Mecca were instructed to bring gold and silver as the medium of payment.

As time passed Hussein was convinced of the need to introduce his own currency. He began by overstriking Maria Theresa thalers with al-Hedjaz but in September 1923 he introduced his own coins. These coins ranged in value from one-eighth to one piastre, minted in bronze, 5-, 10- and 20-piastre coins, minted in silver, and a one-dinar coin minted in gold. These coins were intended to replace the Turkish coins, which were still the dominant coins in circulation. (Many of the Turkish coins had been counter-stamped with ‘Hedjaz’.) However, the gold and silver content of Hussein’s high value coins was questionable and insufficient coins had been minted. Therefore, after a short period most of the coins disappeared from circulation.

By the time Hussein abdicated in favour of ‘Ali, in October 1924, the situation had not improved and the Hedjaz remained burdened with multiple currencies in circulation. It was into this confusion of currencies that Habib Lotfallah arrived in 1925 with his proposal to establish a bank of issue. By the time he submitted his proposal to ‘Ali there was sufficient expectation that paper money could be used with some success in the Hedjaz, due to the earlier circulation of Ottoman paper money and the later use of Egyptian and Indian banknotes. Lotfallah convinced King ‘Ali and his advisers that he could establish a bank that would operate from Jeddah and benefit the kingdom. On 22 Shawwal 1343 (6 May 1925) ‘Ali and his advisors considered Lotfallah’s proposal and on the following day signed the decree that gave Lotfallah his right to operate a bank in the Hedjaz. The decree is as follows:

Royal Edict

We Ali-ibn Hussein, King of Hedjaz.

Having studied the report of Prince Habib Lotfallah, submitted to us on 22 Shawwal 1343, with a view to the constitution of the National Bank of Hedjaz and Arabia and,

On the proposal of Our Prime Minister and the Minister of Finance.

Decree

First Article

Prince Habib Lotfallah has the right of constituting a National Bank of Hedjaz without any responsibility falling to the Arabian Government, and of constituting an Arabian company under the name: The National Bank of Hedjaz and Arabia

Article 2

The National Bank of Hedjaz and Arabia will have the privilege of issuing notes to the bearer or on sight; the said privilege will not be granted to any other establishment during the existence of the Company.

Article 3

Our Prime Minister and the Minister of Finance are charged with the implementation of this Decree:

Made the 23 Shawwal 1343

Ali-ibn-Hussein

The Royal Edict was followed by this Ministerial Order:

Ministerial Order

The Council of the Ministers assembled at the Royal Palace on Saturday 23 Shawwal 1343 at 9 a.m. and discussed the report submitted to His Majesty the King by Prince Habib Lotfallah, soliciting the right of constituting a company, which will take the form of a National Bank of Hedjaz and Arabia, subject to the law of the Arabian Government, with headquarters in Jeddah.

Having viewed the laws of the aforementioned Company, the Council grants to Prince Habib Lotfallah the privilege of constituting the aforesaid Bank for a period of one hundred and one years from the date of the Royal Edict.

If the constitution of the aforesaid Company does not take place within six months of the date of the Royal Edict, this privilege will be regarded as null and void.

Submitted to His Majesty the King for approval.

The Ministerial Order was signed by seven of the King’s Ministers.

A subsequent Hedjazi decree of 3 Dhu’l Qa’dah (26 May 1925) confirmed the articles of the Bank and the directors of the bank. One of the conditions of the ratifying decree was that Habib Lotfallah was to be the Managing Director for the first ten years of the Bank’s life and that one of his brothers, Michel or George, was similarly to be the Assistant Director for the first ten years. Printed in French, the statutes of the Bank were published in Cairo and entitled: Statuts de la Banque Nationale du Hedjaz et Arabie (Société Anonyme)

![]() . The capital of the bank was set at 200,000 Egyptian pounds.

. The capital of the bank was set at 200,000 Egyptian pounds.

It is obvious from the concession sought by Habib Lotfallah, and granted by ‘Ali, that he intended the issuance of currency to be one of the principal activities of his Bank. So, it is no surprise to learn that during 1925 he approached a printing company in France with a request to print notes for his bank. The notes were printed, but presumably not made available for delivery until very late that year, or possibly not until 1926. The reason for supposing this is that King ‘Ali had finally been overthrown by ibn Sa’ud and had fled Jeddah on 19 December 1925—ending the Hashimite rule of the Hedjaz. Ibn Sa’ud then became King of the Hedjaz and Sultan of the Nejd. By the time the banknotes were ready for delivery, there was no Hashimite government in the Hedjaz under which they could be authorized to circulate. Consequently, the banknotes were packed into cash boxes owned by Habib Lotfallah and placed in storage (believed to be in France).

The banknotes prepared for Habib Lotfallah are an interesting set of notes, all the more for not usually being seen in colour. The first thing that strikes the observer is the coloured patterns of rich and subdued hues, with the back of each note being particularly colourful. One intriguing aspect to these notes is the use of the title ‘The Arabian National Bank of Hedjaz’ to designate the issuing authority. The statutes of Habib Lotfallah’s bank had declared his bank to be the ‘National Bank of the Hedjaz and of Arabia’ (i.e. Banque Nationale du Hedjaz et d’Arabie) and it is not known whether the form of the title adopted for the banknotes was due to a misunderstanding, an error in translation, or whether Habib Lotfallah made a deliberate change to the name of the issuing authority on the banknotes.

There were five denominations prepared for issue, in the values of: 1, 5, 10, 50 and 100 Arabian pounds ![]() , which, incidentally, were intended to be equivalent in value to Egyptian pounds. There is much common text on each denomination, which is written in both Arabic and English. The choice of these languages is obvious, as Arabic was the first language of the inhabitants of the Hedjaz and English was the language of the empire that protected the kingdom.

, which, incidentally, were intended to be equivalent in value to Egyptian pounds. There is much common text on each denomination, which is written in both Arabic and English. The choice of these languages is obvious, as Arabic was the first language of the inhabitants of the Hedjaz and English was the language of the empire that protected the kingdom.

The English text at the top of each note reads:

The Arabian National Bank of Hedjaz

Issued under decree dated 23 Shawal 1343

Immediately below is Arabic text which states:

The Arabian National Bank of Hedjaz

I promise to pay on demand a sum of Five Hedjazi Pounds to the bearer

This note issued under decree dated 23 Shawal 1343

(The use of the phrase ‘Hedjazi Pounds’ in this text, as opposed to ‘Arabian Pounds’ is discussed below.) To the lower left on each note is written the denomination in English, for example ‘One Arabian Pound’, while the following are written in English and Arabic:

• the place of issue, which is ‘Djeddah’, and

• the date of the decree, which is ‘23 Shawal 1343’.

To the right-hand side of each note is the following text, once again in English and Arabic:

• ‘For the Arabian National Bank of the Hedjaz’

• the signature of H. Habib Lotfallah (signed in Latin and Arabic scripts), and

• the word ‘Governor’.

On each note the denomination is written in western and Arabic numerals. Above or

beside the western numerals are the letters ‘L.A.’, which represent ‘Arabian Pounds’

![]() . Over the Arabic numerals is written the value of the note in Arabic text, with the Arabic word ‘Junaih’ being used for ‘Pound’. The serial numbers appear on the notes in the top right and bottom left, except for the 100-pound note, where they appear in the top left and bottom right. Interestingly, on the unissued and specimen notes observed for this study, there is a prefix of the Latin letter ‘A’ for the serial numbers on the 1- and 10-pound notes, but not for the other denominations.

. Over the Arabic numerals is written the value of the note in Arabic text, with the Arabic word ‘Junaih’ being used for ‘Pound’. The serial numbers appear on the notes in the top right and bottom left, except for the 100-pound note, where they appear in the top left and bottom right. Interestingly, on the unissued and specimen notes observed for this study, there is a prefix of the Latin letter ‘A’ for the serial numbers on the 1- and 10-pound notes, but not for the other denominations.

Several of the illustrations on the banknotes at first appear incongruous, as why would illustrations of places outside the Hedjaz be illustrated on banknotes intended to circulate in the Hedjaz? The illustrations used on each note are:

The simple reason for the use of these illustrations, that included buildings and scenes outside the Hedjaz, is that Habib Lotfallah was an Arab nationalist and he anticipated that, one day, his notes would circulate not just in the Hedjaz but in all Arab countries. This is why the title of his bank, no matter in which form, always used the words ‘National’ and ‘Arabia’ (or ‘Arabian’) and why illustrations from Lebanon, Syria and Iraq are used on the notes.

The use of King Solomon’s Temple on the 10-pound note may at first appear incongruous

![]() , however it matches the ambitions of Habib Lotfallah. Firstly, Lotfallah was a Christian and he shared the beliefs of the Old Testament. Secondly, in his Arab nationalist beliefs, he expected Christian, Jew and Muslim to live in harmony in Arabia as, at this time, there was so little of the tension that has disturbed the region in recent years.

, however it matches the ambitions of Habib Lotfallah. Firstly, Lotfallah was a Christian and he shared the beliefs of the Old Testament. Secondly, in his Arab nationalist beliefs, he expected Christian, Jew and Muslim to live in harmony in Arabia as, at this time, there was so little of the tension that has disturbed the region in recent years.

The back of each note has the name of the issuing authority in Arabic and the numerals for the denominations in western and Arabic numerals. In the same manner as on the front of the notes, the letters ‘L.A.’ appear above the western numerals at the centre left and the Arabic text stating the value of the note appears above the Arabic numerals at the centre right. The Arabic text for the 1-pound note reads simply as ‘Arabic Pound’, while the text on the 5-pound note states ‘Five Arabic Pounds’ and the 10-pound note states ‘Ten Arabic Pounds’. Significantly, on the 50- and 100-pound notes, instead of having ‘L.A’ above the western numerals, these notes have the letters ‘L.H.A.’. This presumably represents ‘Hedjazi Arabian Pounds’, as the Arabic text above the denominations on the back of the notes states ‘Fifty Hedjazi Pounds’ and ‘One Hundred Hedjazi Pounds’ respectively. That this alternative text appears on the back of these two denominations and not on the front, where the text denominates the notes as ‘Fifty Arabian Pounds’ and ‘One Hundred Arabian Pounds’, suggests that Habib Lotfallah made a late change to the notes and that these changes were not incorporated on the back of these two notes. That a change was made during the preparation of the banknotes is supported by the fact that the promissory clause in Arabic text on front of the notes refers to ‘Hedjazi Pounds’ and not ‘Arabian Pounds’. The error suggests Lotfallah originally intended the notes to circulate only in the Hedjaz, by denominating his notes as ‘Hedjazi Pounds’, but then decided that this denomination of currency may limit the wider use of the currency at a later date. Therefore he changed the name of the currency to ‘Arabian Pounds’, but not all references to ‘Hedjazi Pounds’ were altered on the banknotes. The change in the name of the currency unit may have been made at the same time that the title of the issuing authority was reconsidered, if indeed it was altered to ‘Arabian National Bank of Hedjaz’ from ‘National Bank of the Hedjaz and of Arabia’. Ultimately, it is not know whether the tardy retention of the old values on the back of the two high denomination notes was due to an oversight by Habib Lotfallah or due to an error by the printer. In either case, the errors suggest a rather amateurish endeavour in producing the banknotes.

In the centre, on the back of each note, is a coat of arms in a circle, while the rest of the note is filled with coloured arabesques, except for a white area reserved for viewing the watermark. The name of the issuing authority is written in Arabic in a panel at the top of the note, held within a border that encompasses the entire design on the back.

The coat of arms on the back of each note is distinctly European, but elements are pertinent to the Hedjaz. In the centre of the arms is a shield that appears to hold a sabre standing on its end, over which are crossed two lances and to either side are Arab swords. The shield is surmounted by two daggers, above which is a type of hat or crown, all of which are covered by a cape that has ermine on the inside and red on the outside. Above the cape at the top of the arms is a building of a palace or a castle. To either side of the shield, but outside the red cape, are two palm trees and above each palm tree is the flag the Hedjaz. The flag is three horizontal stripes, of black, white and green, with a red chevron on the hoist. (This flag was later used by the Ba’ath Party in Syria and is currently used as the Palestinian flag.)

On the back of each note, printed in very small letters, just within the lower border of the notes, is the printer’s imprint, which reads: GRAVÉ ET IMPRIMÉ PAR DRAEGER, PARIS. This phrase translates as ‘Engraved and printed by Draeger, Paris’. The Draeger family were master printers and publishers with a long tradition. Nicolas Draeger (born 1813) began the family tradition by learning the printer’s trade and settling in Paris. His son Charles (1844–1899) established a typographic shop at 118 rue de Vaugirard in Paris. He became renowned for his quality printing using typography, wood engraving, and chromotypography, and for adopting the modern printing processes of the era, such as half-tone and three-colour process engraving. His three sons, Georges (1869–1945), Maurice (1872–1942) and Robert (1876–1947) continued the family business, ultimately shifting their printing works to Montrouge. Here they incorporated new printing techniques, such as photo-engraving, stereo-typing, electrotyping, and using photogravure for colour printing, as well as establishing a type foundry.

By the 1920s, the Draeger Brothers (Draeger Freres) were printing fine artwork, photographs and quality books. Well known in France for their first-class work, they also became celebrated for preparing high quality advertising posters, often prepared by leading artists. When Habib Lotfallah approached the Draeger Brothers to print his notes, he would have been aware that he was acquiring the services of one of Paris’s premier printers. However, the Draeger Brothers are not known to have printed any other banknotes and this was probably their only commission in this line of work.

The Pursuit of Further Ambitions

Having had his notes printed, Habib Lotfallah saw that there was no possibility of the Hashimite kings being restored to the throne of the Hedjaz and his notes remained in storage. In 1926 he approached ‘Abd al-Aziz ibn Sa’ud and sought permission to operate the Arabian National Bank of Hedjaz in the territories now under his control. A reply from Sheikh Hafez Wahba, Counsellor to ibn Sa’ud, stated that the Bank could operate as a commercial entity until the new government had consolidated its control in the Hedjaz. Ibn Sa’ud also agreed that the Arabian National Bank of Hedjaz could operate as a state bank, on condition that the Bank loan ibn Sa’ud 100,000 pounds, repayable over ten years with interest. Habib Lotfallah and his directors considered ibn Sa’ud’s proposal in 1927 and deliberated whether they should realize part of the Bank’s capital, to satisfy the demand. Agreement was made to follow this policy and by 1928 a portion of the bank’s capital had been liquidated to meet ibn Sa’ud’s demand. However, it was then recognized that it was not possible to realize sufficient capital and the project to raise 100,000 pounds foundered. (Many years later Habib Lotfallah stated that he was unwilling to give the loan to ibn Sa’ud ‘on principle’.)

Although his banknotes had not been released into circulation, Habib Lotfallah claimed that his bank did commence operations. According to correspondence sent to the British Colonial Office by Habib Lotfallah, the Arabian National Bank of Hedjaz operated from Djeddah, Suez, Cairo and Port Said, although he does note in one letter that the transactions were very limited. Evidence that his bank actually operated from any location is absent, apart from the claims by the Prince. If the bank did operate in any form from any one of the four nominated locations, then it is not known when the bank began operations and when it ceased. However, there is evidence that steps were taken to open a branch of the bank in Aden.

In 1928 Hassan Anis Pasha sought, through the British Colonial Office, to open a branch of the Arabian National Bank in Aden. He was advised that no special authorization was required to open a bank in Aden and that he should approach the local authorities with his request. However, he was also informed that the local authorities felt there was insufficient business for another bank in Aden. It is probable that Habib Lotfallah had negotiated with Hassan Anis Pasha to open a branch of the Bank in Aden but, as the activities of the Bank were curtailed in the Hedjaz, Hassan Anis Pasha did not pursue the matter and nothing further came of the request.

The notes of the Arabian National Bank of Hedjaz languished in storage for some years. However, in 1929 Habib Lotfallah was stirred into action due to activities in Transjordan and Iraq. In August 1921 King Faisal, the son of King Hussein of the Hedjaz, was placed on the throne of Iraq by the British, who were administering the territory under a mandate of the League of Nations. Indian rupees were circulating in Iraq but there arose a strong nationalist movement seeking to implement a national currency for Iraq. The British sent Sir E. Hilton-Young to Baghdad in 1925 to study the situation and he recommended the introduction of a currency board, with the board based in London but which would issue banknotes on behalf of the Government of Iraq. When presented with this proposal in 1926 the Iraqis objected strongly, as the currency was to be under the control of the British, and the matter was not resolved. At the same time, similar issues arose in Transjordan where the British had installed Abdullah, another son of King Hussein, as the Amir. In Transjordan, the notes of the Palestine Currency Board were circulating and there were similar nationalist sentiments that sought Transjordan’s own currency.

It was into this turmoil that Prince Habib Lotfallah stepped in 1929, with a vision of establishing his bank in Transjordan and Iraq. Lotfallah initially discussed his proposal with Faisal and Abdullah and even submitted a plan of his proposal to Abdullah. Lotfallah’s proposal for establishing his ‘National Arabic Bank’ in Amman was conditional on the government of Transjordan making Lotfallah’s bank the government’s official bank. Lotfallah’s proposal also referred to the issuance of banknotes, backed by English sovereigns, to replace the notes of the Palestine Currency Board; as well as indicating that loans could be made to the Agricultural Bank (which was in financial difficulties).

Apparently unsuccessful in his direct approach to Amir Abdullah and his government, Habib Lotfallah determined that he should seek British approval for his scheme. To this end he enlisted the assistance of Cecil L’Estrange Malone, a member of the British Parliament and a friend of the Prince. Habib Lotfallah was not adept at writing English and his spoken English was imperfect. Therefore he enlisted Malone M.P. to translate and submit his proposal to the appropriate government authorities. Approaches were made to the Colonial Office and the Foreign Office, with the object of gaining official British sanction for opening his bank in Iraq and Transjordan and be given the right to issue banknotes in both territories.

Following the receipt of their correspondence, Prince Lotfallah and Cecil Malone were given the courtesy of an interview and met with William Lunn Esquire M.P. an Under-Secretary of State in the Colonial Office. Although he was given the interview, Prince Lotfallah failed to impress anyone in the Colonial Office. His dubious title of ‘Prince’ made some people wary of him and his scheme and his objectives were not always lucid. He wanted British support, but he was unable to be specific in the support he was seeking. He apparently didn’t understand that licences for opening banks in both territories, i.e. Iraq and Transjordan, were the responsibility of local authorities and not the authorities based in London. His desire to obtain the British Government’s sanction for issuing his notes seems to have been a major objective, in which he failed. He also wished to receive introductions to the leading bankers in England, in the hope that they would finance his project. Lotfallah claimed to have been in discussion with Barclays Bank, but it is doubtful they intended to support his project. Claims by Lotfallah that his bank had its head office at Jeddah and branches at Cairo, Suez and Port Said, which had ‘been working quietly for four years’, appeared to the Colonial Office to be lies, as they found no evidence of any activity of his bank; and unsupported claims such as this could not have helped his cause. (Later evidence would show that the bank had been operating as a private concern in a very narrow manner.)

Shortly after Lotfallah and Malone opened their discussions with Mr. Lunn, the Under-Secretary was replaced by Dr. Drummond Shiels, who began to deflect further correspondence from the co-conspirators. Whether or not it became obvious to Lotfallah and Malone that the British Government was not going to support their proposal, it is not known. However, support was not forthcoming and it was never going to be forthcoming. The official British position remained that Habib Lotfallah should seek a banking licence in each territory in the usual manner and that currency arrangements in Iraq and Transjordan were satisfactory.

In early 1930 Lotfallah returned to Egypt en route to Iraq, having received communication from one of his brothers that he should come to the Kingdom. While in Egypt on his way to Baghdad he paid a call on the British High Commissioner, Percy Loraine. While extolling the plans he had already placed before Mr. Lunn and Dr. Shiels, he also addressed his plans for the Arabian Peninsula. Lotfallah now proposed to issue his banknotes in a manner similar to traveller’s cheques issued by Thomas Cook, in anticipation that the Hedjazi government of ibn Sa’ud might be convinced of the importance of his bank. This might then lead to the bank being established in the Hedjaz and the banknotes being recognized as legal tender. Lotfallah also expressed an ambition that ultimately there would be three currencies in the Near and Middle East—the Egyptian pound, the Indian rupee, and his Arabian pound, which would be the currency of all Arab-speaking countries in Asia.

However, Lotfallah’s immediate ambitions had been thwarted in November 1929 by Egyptian customs authorities, who impounded a consignment of £200,000 of his banknotes. Evidently, in anticipation that his plans for establishing his Arabian National Bank in Iraq and Transjordan were nearing fruition, he had arranged for the banknotes stored in France to be sent to Egypt. Unexpectedly, the banknotes were seized and held by Egyptian authorities who stated that the notes would be released if the Arabian National Bank of Hedjaz commenced business, otherwise they would be destroyed. It is likely that Habib Lotfallah’s visit to the British Resident on his return to Egypt was in part to seek intercession for the release of his banknotes, although this request is not recorded in any correspondence.

Habib Lotfallah continued to Iraq and joined his brother. After making himself familiar with the ambition of the Iraqis to form a National Bank and to issue their own currency, he dropped the idea of opening a branch of the National Bank of Arabia and set his mind on establishing the National Bank that Iraq was seeking to establish. To this end he submitted a proposal to the Minister of Finance in the Iraqi government, outlining his intentions. The proposal indicated that he and his brothers, as well as a group of English financiers, intend to establish a company with the name of the ‘National Bank of Iraq’ with the capital of one million pounds sterling. Lotfallah was presumptuous enough to state that, of this sum, £500,000 had already been subscribed. Unless he and his brothers were the subscribers of the half-million pounds, it is difficult to know how the amount could have been subscribed so soon and it is probable that the statement was a lie, made in an effort to sway the Iraqi government into accepting the proposal.

While promising that his bank would provide facilities for the economic and financial development of Iraq, Lotfallah did seek some concessions. He wanted exclusive rights to the government’s business and he wanted the bank to have the sole right to issue banknotes in Iraq for a period of one hundred and one years. He promised to back the banknotes issued by his bank with gold bullion, gold coins, English Treasury Bonds, War Loans and any other securities (preferably English). As to the profits of the Bank and the participation of the government in these profits, Habib Lotfallah asked that this matter might be discussed at a later date.

Returning to Paris, Habib Lotfallah enlisted Cecil Malone’s assistance in approaching the Colonial Office with the aim of gaining approval for his new venture in Iraq. The reply from the Colonial Office to Cecil Malone was succinct but comprehensive. The British Government felt that there were adequate banking facilities in Iraq and Transjordan and did not feel that there was room for another bank. Additionally they felt that the currency requirements of Transjordan and Iraq were being adequately met. However, they encouraged Habib Lotfallah to make formal applications to gain banking licences in both countries. In making this suggestion, they pointed out that Habib Lotfallah would need to provide documentation that would satisfy the authorities of his Bank’s financial standing before approving any application. The Colonial Office believed that the Arabian National Bank of Hedjaz was nothing but a façade and by noting this prerequisite they would likely deter any application. Their estimation of the situation proved correct, as Habib Lotfallah’s proposal progressed no further.

Lotfallah’s initial proposal to open a branch of the Arabian National Bank in Iraq and Transjordan, and subsequent proposal to open the National Bank of Iraq under his control, appear to have suffered from several problems. Firstly, his proposals were not being seriously considered by the British, who were not actively discouraging Lotfallah, but who were determined to frustrate his ambitions should it look as if his projects were nearing fruition. Habib Lotfallah was considered by several government officials to be completely untrustworthy and his schemes a sham. Secondly, in the matter of the National Bank of Iraq, Lotfallah was just a little too late on the scene. His proposal to the Iraqi Minister of Finance was dated 19 March 1930, but on 17 March 1930 a proposal to create the Iraq Currency Board was approved by the Iraqi Cabinet following a recommendation by the Minister of Finance to implement Britain’s proposal of 1926. Although the Currency Board was in no way a National Bank, it was established to issue currency in Iraq. Thus, by the Iraqi government accepting the introduction of a Currency Board, they had no need of Habib Lotfallah’s bank of issue.

In Search of Ambitions Unfulfilled

Habib Lotfallah’s efforts to gain support from ibn Sa’ud in 1926 and 1927 had faltered in 1928, after a failed attempt to raise the required £100,000 by realizing part of the capital of the Arabian National Bank of Hedjaz. Why the decision to raise the cash and supply it to ibn Sa’ud was not carried through is not clear. However, in 1932 Prince Lotfallah again sought to establish his bank in Arabia. Evidently, at the same time a gentleman by the name of Abdul Hamid Shedid was negotiating with ibn Sa’ud with the same objective of establishing a national bank in Arabia. Abdul Hamid Shedid was representing the former Khedive of Egypt and his scheme, although ultimately unsuccessful, seems to have been preferred to that proposed by Lotfallah. Nevertheless, in 1934 Habib Lotfallah was invited by ibn Sa’ud to meet him in Taif near Mecca in order to investigate the possibility of establishing his bank in the Arabian Peninsula.

Ibn Sa’ud had been concerned for a number of years at the problem of money supply and exchange rates during the annual pilgrimage to Mecca and he sought solutions to alleviate the problem. It is probable that he entertained the proposals by Habib Lotfallah and Abdul Hamid Shedid as possible solutions to the problem. Evidently Prince Lotfallah’s proposal was unsuccessful, although correspondence by Lotfallah from a later period indicates that ibn Sa’ud agreed to let the Arabian National Bank of Hedjaz operate on the condition that the Bank could show strong financial backing. It is possible that the Prince sought support from British financial institutions at this time, which was not forthcoming, and that this was a contributing factor to the failure of the bid.

Around this time the Arabian National Bank of Hedjaz was all but wound up, probably due to the failure of the bid to win ibn Sa’ud’s approval. Whether Lotfallah and his brothers simply wished to wind up affairs or whether they wished to realize the remaining assets of the bank is unclear, but it seems that there was an intent to cease what little activity the bank was undertaking. It might also be assumed that, at this stage, Habib Lotfallah felt his ambitions for his bank would never be realized.

However, as the world drifted toward war in 1939, Habib Lotfallah re-opened his correspondence with the British Colonial Office. Once again enlisting the services of Cecil L’Estrange Malone as an intermediary, Lotfallah contacted the Secretary of State for the Colonies, Malcolm MacDonald, who replied to Malone offering the Prince an interview. Malone made known MacDonald’s response to Habib Lotfallah and in a reply to his confidant, Lotfallah shed some illumination on the activities of his bank.

Lotfallah claimed that he had in the past used the services of a Mr. Foa, a director of the former Anglo-Egyptian Bank, to make representations on his behalf to financial institutions such as Lloyd’s Bank, Barclay’s Bank and the Imperial Indian Bank. He indicated that communication with these institutions invariably stalled when it became known that support from the British government was not forthcoming. Exactly what was raised with the financial institutions is not known, but with the knowledge of Lotfallah’s correspondence with the Colonial Office, it is probable that the tenor of any discussion centred around the Arabian National Bank of Hedjaz operating as a bank of issue, rather than a commercial banking venture. As such, it is not surprising that the commercial banks failed to acquiesce to any plans if support from the British government was not forthcoming.

Lotfallah also claims at this point that 500,000 pounds of his banknotes were printed and that the plates for printing the notes were still in tact and could be used to produce further banknotes. This is a tantalizing statement. If only 200,000 pounds of banknotes were seized in Egypt in 1929, then 300,000 pounds must, at this point in time, still have been in storage. Was Lotfallah exaggerating the number of notes printed, or were there in fact notes still available to the Prince?

As to the status of his bank, Lotfallah admits that the bank had gone into voluntary

liquidation around 1934 following his failure to secure an opportunity to operate his bank.

However, he assures Malone that within two months he can arrange for the creation of the state

of United Arabia and that his bank will be the link between the west and the new state.

![]()

Habib Lotfallah’s subsequent interview at the Colonial Office, arranged through the auspices of Malcolm MacDonald, was with Sir John Shuckburgh, to whom the Prince explained his scheme for uniting the Arab countries and establishing his bank. During the cordial interview the obvious difficulties, in seeking the co-operation of various independent states where Britain had little influence, was observed by Sir John. Habib Lotfallah recognized the problem and suggested that he might commence with Saudi Arabia and Yemen before proceeding further. Sir John did not believe the proposal would succeed but he did offer to approach Sir John Caulcutt of Barclays Bank to sound him out, as Habib Lotfallah had indicated that he wished to include some of Britain’s financial institutions in his scheme.

Prince Lotfallah subsequently received an interview with Sir John Caulcutt and although the interview achieved little, he was well received. Sir John, like others with whom Lotfallah had dealt with at the Colonial Office, found it difficult to understand what Lotfallah was seeking of him. However, Lotfallah did seek greater liquidity for his Arabian National Bank of Hedjaz and he suggested that Barclays Bank could acquire fifty percent of his bank. Sir John indicated that if Barclays was to take an interest, they would acquire the whole concern, to which the Prince admitted he was ready to consider such an option. A balance sheet for the Arabian National Bank of Hedjaz from 1934 was made available to Sir John and he noted that a large number of debts owing to the bank were loans made to the Lotfallah family. Despite suggesting that Barclays could get involved in the Prince’s bank, it became evident that they would not. During the interview, Sir John also raised the matter of an advance made by Barclays Bank to the Prince some years ago, which had not been repaid.

Sir John reported the outcome of his interview with Habib Lotfallah to Sir John Shuckburgh and offered to request a current financial statement from the Prince, with the object of establishing that the Prince did not have the wherewithal to continue with his proposed scheme.

At this stage, a new player entered the arena, Mr. A. C. Bossom M. P. Mr. Bossom had befriended Prince Lotfallah and sought to assist him in his schemes. Following meetings with Mr. MacDonald at the Colonial Office and Mr. Bagallay at the Foreign Office, Mr. Bossom managed to gain an interview for Prince Lotfallah at the Foreign Office on the condition that the Prince could show that his proposed bank was financially viable.

A letter from Prince Lotfallah to Mr. Bossom attempted to represent his bank in favourable light by stating that the capital of the bank was £200,000 and that the accounts of the bank were audited by Price Waterhouse and Company. He again declared that banknotes to the value of £500,000 had been prepared, although nothing was mentioned of the notes seized by the Egyptian authorities in 1929. He also stated that he had no concerns in recruiting staff and that he intended to commence his bank in a small way, prior to expanding to all Arab countries.

Mr. Bossom, on the strength of Habib Lotfallah’s reply, obtained an interview with Mr. Bagallay. At this meeting Habib Lotfallah simply requested that the British Government guarantee his bank note issue to the value of £200,000 (not the £500,000 mentioned in his correspondence to Mr. Bossom), so that he could establish his bank in Saudi Arabia. Lotfallah was still clinging to the promise made by ibn Sa’ud some years earlier, that he could establish his bank in ibn Sa’ud’s realm if it was backed by the British. Prince Lotfallah emphasized the point that he was not asking the British Government to provide capital for the bank, but simply to provide a guarantee for the note issue.

Around the time that Mr. Bossom was making representations on behalf of the Prince, Cecil Malone resumed his activities and wrote to the Colonial Office seeking to promote the interests of the Prince. With several appeals being made to the Colonial Office and the Foreign Office on behalf of the Prince, it was decided, in an effort to bring the matters concerning the Prince to a conclusion, to accept Sir John Caulcutt’s offer of asking Habib Lotfallah to present his financial position with the supposed intention of Barclays Bank considering his proposals.

A meeting was subsequently held on 8 March 1940 at the Colonial Office. In attendance were Sir John Shuckburgh and Mr. Downie of the Colonial Office, Mr. Coverly-Price of the Foreign Office and Sir John Caulcutt and Mr. Jones of Barclays Bank. Sir John Caulcutt had received an interim report from Barclays Bank in Cairo, which indicated that Prince Lotfallah’s bank had not been functioning since 1934 and that the business of the bank had seemed to consist of loans and discounts to family members. There also appeared to be a loss of £18,000 showing on the books, which was not immediately understood. The status and financial position of the Prince’s bank did not present it as a vehicle by which a national bank of Arabia could be established. Sir John Caulcutt was expecting a detailed report from Cairo, showing the situation of the Bank in 1934, and until this report was received it was decided to leave the matter in abeyance.

On 1 April Prince Lotfallah met with Sir John Caulcutt and Mr. John of Price Waterhouse. A this meeting, Sir John acknowledged that the Prince’s scheme seemed sound but, due to the war, it was not an opportune time to initiate the scheme and Barclays would find it a difficult proposal to support in the current climate. The matter might, Sir John suggested, be revisited after the war.

Habib Lotfallah saw that he was being fobbed off by Barclays Bank, but he clung to the hope that the British Government might still support him. He wrote to the Secretary of State, Lord Lloyd, requesting an interview, but none was offered. By April 1940 the British had learnt that ibn Sa’ud had the lowest opinion of Habib Lotfallah and would not trust him with the formation of the bank unless the British Government took a lead in the project. The various officials who had dealt with the Prince also had no faith in his personal capabilities. While admitting him to be a charming man, his lack of banking experience and his inability to be an instrument of policy in the Middle East almost made him an object of derision in government circles.

On 24 May Habib Lotfallah was given his last interview with Mr Bagallay of the Foreign

Office. The interview became slightly acrimonious as Mr. Bagallay made it quite clear that the

proposals of the Prince would not be entertained by the British Government. Ultimately, the

Prince was dismissed with no room left to doubt the failure of his schemes. However, several

interesting claims were made during this final interview. On being reminded that the British

Government would not support his bank or guarantee his banknotes, the Prince declared that this

did not matter, as the single issue at hand was really the political situation in the Arab countries.

He raised the matter of the failure of the British to maintain the Arab nation as a single entity

after the First World War and indicated that the current war offered an opportunity to reverse the

mistake. He wanted to unite all Semitic races of the Middle East, including Jews, Christians and

Moslems. To achieve this, the personal influence of the Lotfallah family would be used. The

Prince claimed to be the leading power amongst the Freemasons of the Middle East and he

averred that, if it were not for the French, his brother George would have been universally

acclaimed as the King of Syria. The Prince declared his dislike of ibn Sa’ud and of the late King

Faisal of Iraq and he sought the British Government’s assistance in overthrowing the incumbent

administrations in various Arab countries, to be replaced by the Lotfallah family in supreme

command.

![]()

Not surprisingly, Mr. Bagallay took the Prince’s declarations lightly, and indicated that Great Britain would not support his schemes against countries with which the Government had existing treaties. The Prince then threatened to take his scheme for a bank (which he had just declared to be immaterial) to the Americans, suggesting that the British would not appreciate the interference of the Americans in Saudi Arabia. He also complained that, at the time ibn Sa’ud was threatening King ‘Ali in Jeddah in 1925, he had raised mercenaries to fight ibn Sa’ud but was not allowed to engage ibn Sa’ud because the British would not permit him. Had he had his way then, it was insinuated, the current state of affairs would never have eventuated. However, all the threats and theatrics of the Prince did not impress Mr. Bagallay and the end of this interview appears to have marked the end of the Prince’s aspirations for his bank in the Arab countries and, from this point, his project faded and all initiative was lost.

Habib Lotfallah saw out the war in Great Britain, in much the same manner that he had sought refuge in Madrid during the First World War. The possibility cannot be overlooked that the final proposal for his Arabian National Bank of Hedjaz was little more than a scheme to find his way to Britain simply to escape the war on the continent and in Egypt. If this was not his original intent, it was certainly the final outcome.

Conclusion

The story of Prince H. Habib Lotfallah and his Arabian National Bank of Hedjaz spans some fifteen years, from the decree made by King ‘Ali in 1925 to his last bid to the British Government in 1940.

What drove him to establish his bank and, having his immediate objective thwarted in the Hedjaz, why did he seek to launch his bank in Aden, Transjordan, Iraq and then in Arabia? From correspondence generated by Habib Lotfallah, he certainly expressed a desire to use his bank to promote Arab nationalism and he had the ultimate goal of uniting all Arab nations as one country or under one federation. In looking at the original incarnation of the Arabian National Bank of Hedjaz, it appears that Arab nationalism was not his prime objective, although Arab nationalism was an ideal that he shared with King Hussein. Perhaps Habib Lotfallah saw his bank being given a wider audience under the Hashimite kings, but there is always a suspicion that the objectives of Prince Lotfallah were more mercenary.

Despite his declared nationalist intentions, a concession sought by Habib Lotfallah from Amir Abdullah and King Faisal was the entire business of their respective governments. This concession, if given, would have been a financial benefit that would have secured the future of the bank. It is thus difficult to see that the intent behind this concession was anything but financial.

The happenstance of history that saw Habib Lotfallah’s ambitions dashed before him in 1925, at the point of their achievement, must have been a bitter disappointment to the Prince. He spent much of the rest of his life trying to resurrect the opportunity which he had lost. However, while he was able to ingratiate himself with King Hussein and King ‘Ali, it appears that he was similarly alienated over time from Ibn Sa’ud and King Faisal of Iraq.

Although originally on familiar terms with kings, rulers, diplomats and politicians, he was unable to make any real difference in the areas he sought to exploit. Certainly, his quixotic attempts to establish his bank after its initial failure were handled without any real acumen. He seems to have been living in a world where matters were achieved entirely by influence and association and he could not understand that his plans had to be backed by substance, not just by his promises. It is also apparent that, as he grew older, he became an anachronism who was not always well regarded.

The movements of Habib Lotfallah after he left Britain, following the end of World War II, are uncertain. It is known that at some stage he made his way to Lebanon and, after living there for a number of years, he finally passed away in Beirut. Ultimately, his legacy and the legacy of the Arabian National Bank of Hedjaz are several unissued sets of his banknotes. It is assumed that the Egyptian authorities destroyed the notes they impounded in 1929. It can also be assumed that the later claims by Habib Lotfallah that £500,000 of his notes were printed, rather than the £200,000 indicated earlier, is an exaggeration and that no notes of the Arabian National Bank of Hedjaz exist, apart from unissued and specimen notes. Thus ends the story of H. Habib Lotfallah and the Arabian National Bank of Hedjaz.

Images

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

The following people have assisted in this study and their input is appreciated:

This article was completed in June 2005

© Peter Symes