The Primary Producers Bank of Australia, Limited

Peter Symes

In the annals of Australian banking histories, one bank is rarely mentioned—The Primary Producers Bank of Australia, Limited. Operating from 1923 to 1931, it was based on European co-operative banks that serviced rural communities and was probably inspired, to some extent, by a revival of this type of banking in the United States of America in the early twentieth century. Co-operative banks took deposits from farmers and then provided rural or land credits exclusively to farmers, and this was the aim of The Primary Producers Bank.

Initially, a company titled “Land Credits, Limited” was created by Ivo W. Kerr, Harry Roach and others in early 1922. The company was established with a nominal capital of 10,000 £6 shares. The company proposed to commence a banking business offering two per cent interest on current accounts, at a time when the established banks were not paying interest on current accounts. Money was to be loaned to its shareholders on advantageous terms, in the manner of the co-operative banks of Europe and the United States of America.

Harry Roach was elected the first secretary of the company and “organisers” were sent throughout the country to promote the aims of the company. Local primary producers were appointed as directors to local boards and shares of £5 were sold at a premium of £1—although only £1 of the shares was paid up. Within six months the nominal capital had risen to £750,000.

It was to later transpire the founders of Land Credits, Limited, commenced working for their own interests. In July 1922 Harry Roach established General Underwriters Limited, which was to have a nominal capital of £10,000 but the registration of the company, in New South Wales, showed the paid-up capital of the company was £35. This company’s single objective was to take over the brokerage business of John Henry Saunders and Samuel Hood Hammond who had been selling shares in Land Credits, Limited, through their brokerage business. Saunders and Hammond received over £9,900 worth of shares in General Underwriters for the acquisition of their concern. The agreement with Hammond and Saunders, and then with General Underwriters, was Land Credits Limited would pay them 8 shillings and 6 pence commission and expenses for every share they sold in Land Credits. Thus, as Land Credits grew, the commissions became profitable. The dubious aspect of this arrangement was that Roach was secretary to General Underwriters and secretary to Land Credits, while Saunders was a director of General Underwriters and organising secretary of Land Credits.

On 11 December 1922, the directors of Land Credits decided to change the company's name, and at a special meeting of shareholders on 28 December 1922 the alteration to Primary Producers Bank of Australia, Limited, was approved. However, when they approached the Registrar-General of New South Wales to change the name, permission was refused. The decision was upheld by the Department of Justice.[1] Subsequently, an application was made in Queensland to register the company as The Primary Producers Bank of Australia, Limited, with a nominal capital of £2,000, even though the capital and premiums subscribed to Land Credits Limited was in the region of £200,000. The new company was then registered in New South Wales as a foreign company. The strange situation now occurred whereby the directors were operating two companies, one registered in Queensland as The Primary Producers Bank, Limited, and one in New South Wales as Land Credits, Limited.[2]

In early 1923 advertisements appeared in country newspapers throughout Australia, initially in the eastern states, promoting Land Credits, Limited, which was advised would soon become The Primary Producers Bank of Australia, Limited. The institution was promoted as “A much-needed Mutual Banking and Financial Association for the Country Districts” and “Conceived in the Country for the benefit of Country Districts.” The initial directors of the company were Roy Hadley Edols, Harry Milton Carter, Bertram Valentine Bowler, William Johnson, John Fisher and John Wallace Shannon. The state director for South Australia was W.G. Mills, MLC, with Thomas Murray Hall and Fergus McMaster state directors in Queensland, and for Victoria the state director was Sir John W. Taverner.[3]

Promotional material appeared in newspapers of the rural districts, such as:

The great aim is to make the institution the financial buttress of the primary producers, owned and controlled by the primary producers themselves. Though each branch will be an integral part of the general organisation, the capital to start the branch will be subscribed in the district in which the branch is to operate, and the shareholders of the branch elect their local directors who know the farmers, their lands, and needs, and the district, and its possibilities to work with the local manager in an advisory capacity. Such a bank will not only support and advance the primary industries; it will retain the free capital of a district to be available for local general development.[4]

Representatives of the nascent bank, the “organisers,” travelled throughout Australia, holding meetings in rural communities, trying to gather support for the establishment of branches of the new bank. In March 1923 a report from Queensland stated:

Mr. W. G. Williams is in Rockhampton making the necessary arrangements for the extension into Central Queensland of Lands Credits, Limited, which will later be called The Primary Producers Bank of Australia, Limited, a co-operative bank registered in New South Wales which opened its first country branch at Lismore on the 1st instant. The nominal capital of the bank is £1,000,000, of which £630,000 has been subscribed. The shares are being offered to the public as preference shares at seven per cent interest free of state income tax besides participating in all profits. The bank pays two per cent on current accounts (daily balances). It is being established for the sole benefit of the man on the land.[5]

At a meeting to celebrate the opening of the first branch at Lismore, Mr. F. W. Strack,[6] then chief inspector of Land Credits Limited, stated in a speech:

It has been asked, "What need is there for another bank? There are already sixteen banks in Australia, and several savings banks, for a population of about six millions, so why another bank?" I answer that, there may be no need for another bank conducted on exactly the same lines as the present associated banks, but there is great need for a bank on different lines. What called the present banks into existence? Simply a desire to make as big dividends as possible. Was there a desire to help the country? Not the slightest. If a branch bank is ever opened you can be sure it is not for the convenience of the public, but because it is known that good profits are to be made in that particular place. How long do you suppose a branch bank would remain open if it did not show profits? Not one day! Do the present banks, then, fulfil the requirements of the country? Only to a certain extent. Just when, in our somewhat uncertain climate, a producer of the country's wealth needs assistance to tide him over a trying season, is the very time the banks are calling in loans. In that one respect alone, then, the present banks do not meet the legitimate requirements of the country. Frequently it pays a bank better to deal in what is known as foreign exchanges, and they eagerly buy or sell drafts, telegraphic transfers and bills on places abroad, leaving the country comparatively bare of loans at a critical time when help is most needed for production.

Enthusiasm for the new bank was growing and by the end of March a branch was opened in Warwick, Queensland, and in an advertisement to promote the new branch the authorised capital of the bank was now stated to be £2,000,000. The bank offered interest paid quarterly on savings bank accounts, on current accounts and on fixed deposits, and there was no account-keeping fee or charge on exchanges between branches.[7] The payment of interest on current accounts remained unique to The Primary Producers Bank in Australia.

In April a second branch of the bank in New South Wales was opened at Wallendbeen.[8] This was followed by the first branch in Victoria at Quambatook[10] and the first branch in South Australia at Balaklava.[1] In July 1923 the Brisbane branch opened in Edward Street[11] and in the same month the Sydney headquarters opened in Castlereagh Street.[12] The Hobart[13] and Adelaide[14] branches opened in August 1923 and by the end of that month the nineteenth branch of the bank was opened in Launceston.[15] A branch of the bank opened in Young in August 1923[16] and at the opening of this branch, Mr. F. W. Strack, now the General Manager of the bank, stated the paid up capital of the Bank had increased to £4,000,000.[17] An agency of the Young branch was opened at Wombat in September 1923.[18] The first branch in Western Australia was opened at Northam in November 1923[19] and the branch at Wynyard in Tasmania opened in December 1923.[20]

Although the bank was progressing well, in October 1923 friction appeared between Sir John Taverner, chairman of the Victorian local board of the bank, and the board of directors in Sydney. Sir John published a statement in which he accused the central board of a lack of consultation with all board members with regard to the payment of commission on shares to Messrs. Hammond and Saunders, and the establishment of a share-selling department within the bank. Decisions had taken place in Sydney without the state directors being invited to the meeting and he had protested the action. As his protests were disregarded, he announced his intention to resign.[21] Sir John’s announcement was reported across the nation and could not have helped the bank. A two-day meeting in Sydney on 7 and 8 November 1923, organised by the bank and which included the central and state boards, soon resolved the matter to everyone’s satisfaction, with a new scheme for the sale of the bank’s shares to be investigated.[22]

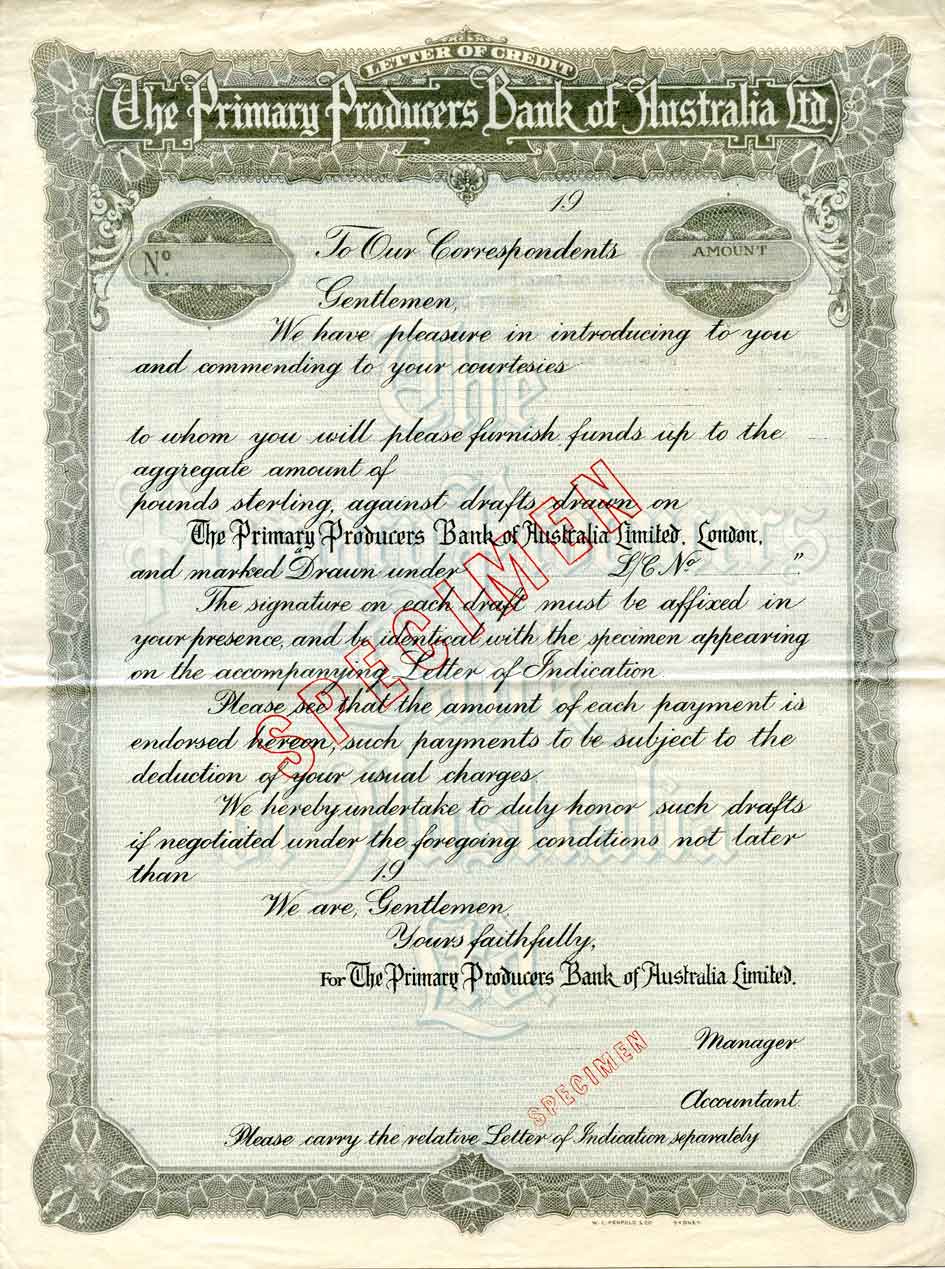

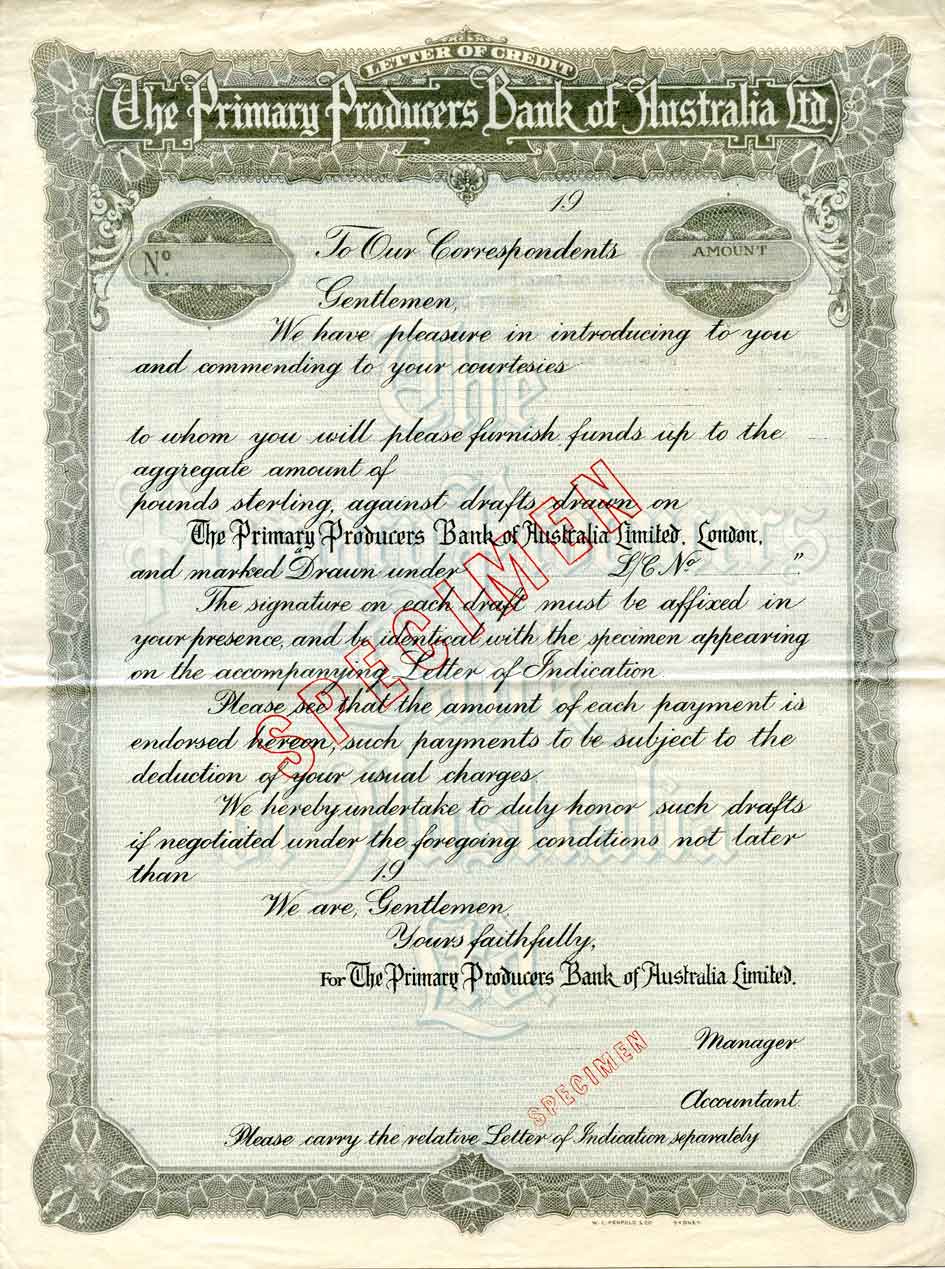

There was evidently some objection to the new bank by the established banks. It was reported they refused permission for The Primary Producers Bank to use the clearing house for clearing cheques. This was asserted in the New South Wales parliament during debate on a bill granting the Bank of New South Wales a new charter.[23] Whether this accusation was true or not, is difficult to determine. Certainly, cheques drawn on The Primary Producers Bank did circulate and they established other financial services common to all banks, such as issuing travellers’ letters of credit.

As the bank’s organisers moved through the country districts, the bank was being promoted by newspaper articles supporting the aims and objectives of the bank, and often denigrating the activities of the established banks.[24] These articles appear to have been supplied to the newspapers by The Primary Producers Bank. Once a branch was established, promotion of the branch in the local and regional press continued through the use of advertisements.

The Primary Producers Bank was never a major player in the economy of Australia, but it had some influence. Rural credits became a part of Australian banking, with the Commonwealth Bank opening a rural credits department by the end of 1925.[25] When Sir George Elliot, Chairman of the Bank of New Zealand, commented on the possibility of rural credit associations or agricultural banks being established in New Zealand, he paid homage to The Primary Producers Bank.

The Primary Producers Bank of Australia, Limited, Sir George Elliot pointed out, was registered in February, 1923, with authorized capital of £4,000,000. Up to September last £2,275,000 had been subscribed. Branches and agencies numbering 71 had been opened in every State of the Commonwealth. For the year ended February last [1925] deposits amounted to £937,368, and advances to £750,401. There were 9,000 shareholders, and 90 per cent of the capital was owned by farmers. It was managed by bankers, but policy was directed by men on the land. The Primary Producers Bank was in the same position as every other bank in Australia, except the Commonwealth Bank.[26] It received no favours from the Government.[27]

While The Primary Producers Bank appeared to be faring well, there was some discontent amongst the shareholders. In 1929, after six years of trading, no dividend had been paid on the shares. The chairman of the bank replied to this criticism by saying that should interest not have been paid on current accounts, that amount would have been added to the profits of the bank and could have been paid as a dividend. Additionally, the shares of the bank were seven per cent preference shares and each year the value of the shares increased by that amount.[28]

The Great Depression affected the economy in Australia, but it did not have a significant effect on the banks. While The Primary Producers Bank had been affected, with profits significantly falling from 1929, it was still in a sound position in 1931. Advances never exceeded deposits and the cost of establishing the branches and agencies, and the commission on the sale of shares, had been funded by the £1 premium on the sale of shares.[29] Although, it has been asserted the construction of bank premises had been undertaken at the cost of profits.[30]

On Monday 24 August 1931 The Primary Producers Bank suspended payment and on Tuesday the headquarters in Sydney and 40 branches in six states did not open for business. At the time the bank suspended payment it was still solvent. The economic outlook in New South Wales had received a setback after the election of Mr. Jack Lang’s government, which promoted financial policies that were pilloried by the banks and by the press. Panic soon commenced, with depositors withdrawing their funds from the State Bank of New South Wales, at that time the second largest institution of its type in the world.[31] This run on the bank forced it to close its doors and ultimately led to it being taken over by the Commonwealth Bank.

The run on the State Bank caused the directors of The Primary Producers Bank to fear a run on their bank, a fear possibly heightened by their paucity of cash reserves.[32] Directors of the Bank approached the National Bank of Australia, to sound out the possibility of a merger, which was rejected,[33] and an approach to the Commonwealth Bank for assistance was also made. While the Commonwealth Bank provided a small loan,[34] they declined further requests for support.[35]

During its final weeks, before The Primary Producers Bank closed its doors, the Bank of New South Wales investigated the affairs of The Primary Producers Bank to determine whether they should take it over. An internal report stated the “advance business” of The Primary Producers Bank was in a rotten condition and the acquisition of the Bank would be expensive at any price.[36] As well as seeking amalgamation with Australian trading banks, The Primary Producers Bank also sought amalgamation with overseas financial groups. The Commonwealth Bank considered arranging joint action with the trading banks to avoid closure of The Primary Producers Bank, but the other banks decided against the proposal.[37]

The uncertain times also saw the failure of the State Bank of Western Australia, which was taken over by the Commonwealth Bank in 1931 under similar circumstances that affected the State Bank of New South Wales. The Federal Deposit Bank[38] also failed in 1931 under similar circumstances to The Primary Producers Bank, with that bank also being solvent at the time it suspended payment.

There was a deal of speculation at the time on the fate of The Primary Producers Bank, whether it might be taken over, whether depositors would receive their funds, and whether shareholders would have to pay a £4 call on their shares (where only £1 of each £5 share had been paid). The bank assured the public they would pay twenty shillings in the pound once all assets were realized.[39] Despite continued speculation the bank might be taken over, it was soon in liquidation.

As it transpired, over a number of years, payments were made to creditors and, ultimately, in 1935 nineteen shillings and nine pence in the pound was paid after the remaining assets were vouched for, to the sum of £200,000. In the final winding up, the court advised the liquidators the English investors should be paid twenty shillings in the pound, as they had not received notice of the final meeting of creditors. Dissenters of the agreement at the final meeting of creditors could also apply for payment of twenty shillings, if done so within three months.[40]

The following table shows how The Primary Producers Bank fared from 1924 through to the suspension of payments. The bank had been progressing well for a number of years, even if it was, within Australia, a small banking concern.[41]

| |

£ Deposits |

£ Advances |

£ Profit |

| 1924 |

300,221 |

254,631 |

975 |

| 1925 |

937,369 |

750,401 |

3124 |

| 1926 |

1,362,232 |

1,183,468 |

3592 |

| 1927 |

1,551,283 |

1,388,734 |

5204 |

| 1928 |

1,777,398 |

1,537,788 |

5637 |

| 1929 |

1,903,896 |

1,769,650 |

7073 |

| 1930 |

1,895,727 |

1,804,559 |

2828 |

| 1931 |

1,483,845 |

1,592,318 |

990 |

The dramatic drop in deposits between 1930 and 1931, over £410,000, shows how the withdrawal of deposits was affecting the bank, and the fall in profits from 1929 are possibly due to the impact of the Great Depression. The fall in deposits has also been blamed on the drop in prices of primary products.[42]

Sources:

- Blainey, Geoffrey 1958 Gold and Paper, A history of The National Bank of Australia, Georgian House, Melbourne.

- Fitz-Gibbon, Bryan and Marianne Gizycki October 2001 A History of Last-resort Lending and other Support for Troubled Financial Institutions in Australia Reserve Bank of Australia. (https://www.rba.gov.au/publications/rdp/2001/pdf/rdp2001-07.pdf)

- Harvey, Gerald C. 1980 The Origins, Evolution and Establishment of the Rural Bank of New South Wales 1899 – 1979 Published by the author, Sydney.

- History of the Commonwealth Bank (http://www.cirnow.com.au/history-of-the-commonwealth-bank/)

- Holder, R.F. 1970 Bank of New South Wales, A History Angus and Robertson, Sydney.

© Peter Symes 2018

Notes

- [1] It was understood the Justice Department expressed a view: that such action would possibly “mislead the public.” (Smith’s Weekly 14 July 1923.)

- [2] Smith’s Weekly 14 July 1923, page 1.

- [3] The Scone Advocate 9 January 1923, page 4.

- [4] Armidale Chronicle 20 January 1923, page 3.

- [5] Morning Bulletin (Rockhampton) 3 March 1923, page 8.

- [6] Mr. Frederick William Strack started his banking career with the Bank of New Zealand, then moved to the Union Bank where he worked in Australia, New Zealand and London. In late 1912 he was one of the first men to be asked to join the Commonwealth Bank when that bank was established, joining on 1 January 1913. During World War I he was in London, on behalf of the bank, working with the Australian forces, including prisoners of war, in England and on the continent. He wrote several text books on banking and these were widely used at the time.

- [7] Warwick Daily News 22 March 1923, page 4.

- [8] Cootamundra Herald 25 April 1923, page 2.

- [9] Farmers’ Advocate 26 April 1923, page 2.

- [10] The Register 11 May 1923, page 10.

- [11] The Brisbane Courier 19 July 1923, page 13.

- [12] Sydney Morning Herald 20 July 1923, page 6.

- [13] Examiner (Launceston) 16 August 1923, page 5.

- [14] News (Adelaide) 23 August 1923, page 4.

- [15] Daily Telegraph (Launceston) 30 August 1923, page 5.

- [16] Cootamundra Herald 28 August 1923, page 3.

- [17] Young Witness 4 September 1923, page 4.

- [18] Young Witness 15 September 1923, page 2, and 18 September 1923 page 4.

- [19] The West Australian 18 October 1923, page 7.

- [20] Examiner (Launceston) 6 December 1923, page 2.

- [21] Farmer’s Advocate 26 October 1923, page 2.

- [22] Farmer’s Advocate 9 November 1923, page 2. Sir John Taverner died a month later in December 1923 while opening a new branch of the Primary Producers Bank at Doncaster in Victoria. Sir John had been a member of several Victorian governments and Victoria’s Agent-General in London for nine years. (Maitland Weekly Mercury 22 December 1923.) Undoubtedly, his stand on the matter of commission on the sale of shares brought some sense to the processes of the central board of the bank.

- [23] Sydney Morning Herald 12 September 1923, page 14.

- [24] An example of a “contributed” article appears in The Horsham Times on 16 October 1923, page 6.

- [25] Register (Adelaide) 2 January 1926. The Commonwealth Bank (Rural Credits) Bill was passed on September 14, 1925 (History of the Commonwealth Bank). The Government Savings Bank of New South Wales, known as the State Bank of New South Wales, did have a Rural Bank Department from 1920, formerly the Advances Department. After this bank was taken over by the Commonwealth Bank, the Rural Bank was established in 1933 and based on the Rural Bank Department. (Harvey.)

- [26] The Commonwealth Bank held special privileges as the government bank.

- [27] Register (Adelaide) 2 January 1926.

- [28] Brisbane Courier 23 May 1929.

- [29] Horsham Times 28 August 1931, page 8.

- [30] Blainey page 335.

- [31] History of the Commonwealth Bank.

- [32] Blainey page 336.

- [33] Blainey page 336.

- [34] The Commonwealth Bank provided an unsecured overdraft of £100,000 and a loan of £295,000 secured by government bonds, a fixed deposit at another bank and the bank’s premises. (Fitz-Gibbon, page 40.)

- [35] Fitz-Gibbon, page 74.

- [36] Holder, page 724.

- [37] Fitz-Gibbon, page 40.

- [38] Anticipating a run, the Federal Deposit Bank approached the Commonwealth Bank for assistance. The Commonwealth Bank provided a small loan but declined further requests for support. (Fitz-Gibbon, page 74.)

- [39] Horsham Times 28 August 1931, page 8.

- [40] Sydney Morning Herald 30 October 1935, page 15.

- [41] At the time of its failure, it held less than half a per cent of the total Australian bank deposits. (Fitz-Gibbon, page 39.)

- [42] Blainey page 336.

HOME PAGE